One of the stories my mom used to tell people about me when I was a kid was that I asked for a Barbie when I was two. She told toddler-me that I had to learn how to tie my shoes before I could have a doll with bigger boobs than hers. And so, the story goes, I learned how to tie my shoes that same day. Back then, velcro wasn’t really a thing yet, so shoe-tying was a much earlier developmental milestone than it is today. But I was still ahead of the curve, as far as hand-eye coordination and perhaps a love of Barbie, which was probably why my mom liked to tell the story.

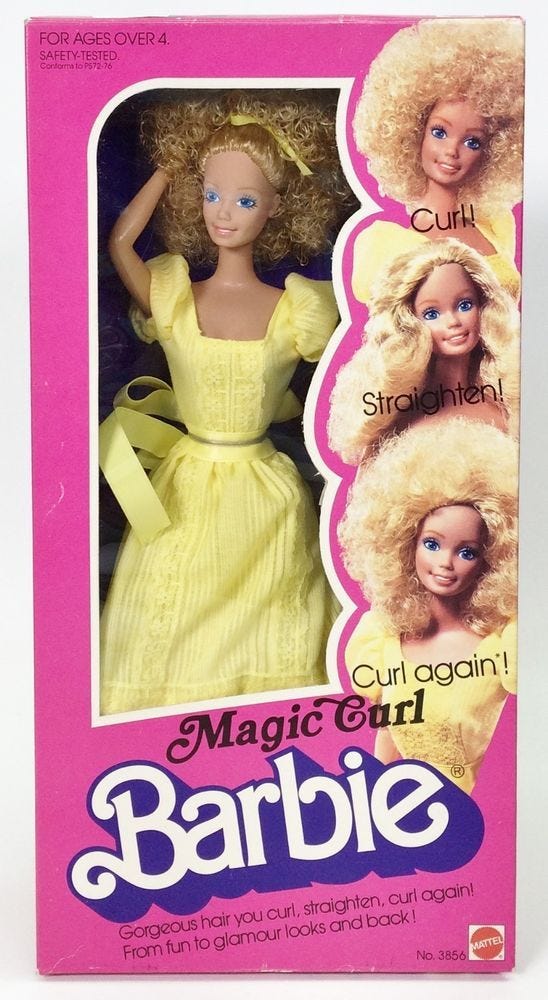

I don’t remember how badly I wanted a Barbie. I don’t remember where I saw the doll or what about her appealed to me. Did I see her in a television commercial? Or pass her in the aisle of a store? As a parent, I know it doesn’t take much to make a kid want something. I vaguely remember getting a Barbie for what had to have been my third birthday. The experience of unwrapping Magic Curl Barbie (released in 1981), who came with curlers and a yellow dress, exists at the very rim of my consciousness. Mostly, I remember having her.

Barbie was my favorite toy, and through the years I collected many of them until I stopped playing with toys altogether in the sixth grade. Most of my Barbies were the standard blondes, but I had Asian and Black Barbies; I remember coveting the Dolls of the World in the JC Penny holiday catalog, though I never saw those ones in the stores where we lived in northeastern Ohio. I usually played with my Barbies alone in my room. I had a brother who was a year younger than me, and all my nearby cousins and parents’ friends’ kids were boys. And so it was me and my imagination and all my pretty dolls.

She was a vehicle for my exploration. What would it be like getting dressed up in a dress like that? What would it be like to go on a road trip in a pink Corvette? What would it be like to be surrounded by a bunch of other girls? What would it be like to have a boyfriend? Or a date? Barbie wasn’t changing diapers or cooking or cleaning. She was getting dressed, getting ready to live.

But no matter how much I loved Barbie, I can’t ignore the fact that some people hate her. Over the weekend, The New Yorker published an essay by a writer much smarter than me about how much she hates Barbie. And she makes a strong case. I guess in the sixties, Barbie came with accessories like a scale that read 110 pounds and a book about dieting. Some even say she is a symbol of white supremacy because of her blonde hair. Maybe my ability to ignore all of this and love Barbie anyway is because, by the time I was playing with her, Barbie came in all races. She wasn’t dieting; she was a doctor and an astronaut and a career woman. She had adapted with the times or perhaps stepped into her role as a cultural icon.

I can’t ever remember feeling threatened by Barbie’s beauty. When I was comparing myself to others, it was to the girls at school and the girls in Seventeen and Teen magazines. I never looked at myself in the mirror and wished I looked like one of my toys. But I get it. Barbie’s figure and doll-like features are not realistic. Reading the anti-Barbie essays, it seems I must be lucky that Barbie didn’t ruin my life. I have a healthy relationship to food and my body is what it is. I’m also in my forties, old enough to understand my body is my vessel rather than a marker of my value. But when I look back on my mom and the story of how I tied my shoes at two to get a doll with bigger boobs than hers (a comment steeped in comparison), maybe she told people that in her own defense for buying a controversial toy for her daughter.

To me, Barbie is about femininity that isn’t sexualized—femininity for femininity’s sake, not femininity for the male gaze. This is something I’ve always been able to appreciate, even when I haven’t aspired to it myself. Since her white, blonde beginnings, Barbie has become more inclusive, first through skin color and most recently through body shape. Because of Greta Gerwig’s new movie, Twitter over the past few months has been a treasure trove of Barbie photos and memories. And not all, but most of the sentiment surrounding her is positive.

I have followed the Barbie film since it was first announced last year, and in all my life I can’t remember ever wanting to see a movie more. I bought tickets over a week before the release to make sure we’d have good seats. I have looked at all the press photos and watched the trailers and absorbed the details as they became available. I have connected with it as much as a busy mom of three can connect to anything without deterioration in primary function.

My daughter and I went to see it the day it opened. And it occurred to me, sitting there in the darkened theater awaiting my first glimpse, that I have come full circle. I am that little girl who was so taken with Barbie that, when issued an ultimatum, took the laces by the bunny ears and tied.

The movie is about Barbie having an existential crisis in Barbieland, and she goes on a misguided quest to fix things by entering the real world and helping the girl who’s playing with her. America Ferrara plays a Barbie designer who works for Mattel. Her daughter has recently stopped playing with the dolls and entered those sullen early teen years when we realize, if we haven’t already, just how unfair the world is. And early in the film, Ferrara delivers a monologue that summarizes all the ways being a woman is so complicated. We’re supposed to be pretty, but not too pretty. We’re supposed to want to be healthy, but we also have to be thin. We’re supposed to love motherhood, but we can’t talk about our kids too much. The critics say the movie’s messages aren’t revolutionary or original, but where else in a pop culture phenomenon so large and universally appealing have we been able to say how hard it is to be a woman? When has Barbie been able to say it for all of us like this?

One of Barbie’s first clues that something in her plastic world is off is that she finds cellulite on her thighs. This is, of course, the most universal physical imperfection of womanhood. Even skinny women have cellulite or will soon enough. This aspect of the film has been criticized because I read in another essay that apparently someone somewhere has also created a Barbie cellulite treatment, which undercuts the film’s message about beauty in imperfections. This all feels very much like a problem of capitalism. When everything is an opportunity to make money, the meaning gets lost.

Barbie’s existence is as complicated as womanhood. Because there is Barbie, who we love, but there are also the corporate overlords who only care about making money. Profit is the real reason they’ve kept Barbie relevant all these years. And that’s complicated because in doing so, they may have also made little girls feel happy and empowered to be something besides a mom, or something in addition to a mom. I know corporations are bad and plastic is bad and all of that. In this case, though, Mattel has also given us what we want, something that ignites our imaginations, something that might help us get through the hard days of reality. Mattel may be making money for it, but they also let Greta Gerwig create a delightful, wonderful thing. And maybe the movie is shallow and corporate-sponsored. But Barbie is also really great.

When I think about the little girls who felt fat and ugly because of Barbie, I don’t feel mad at Barbie. I’m mad about whoever told those little girls that they needed to view the world in terms of comparison. That the existence of beauty in someone or something else somehow negates their own beauty. I’m mad at whoever made them think all girls and women aren’t pretty regardless of what they look like. But I don’t think the norm should be comparing ourselves to toys. I wish we would look harder at that impulse to compare, which feels more pervasive than the Barbie movie’s marketing campaign.

Maybe Barbie has damaged me. Maybe I’m a hollow shell of the capitalism that raised me. Maybe my thinking is so warped that I can’t tell that I should have been blaming my toys all along for everything that’s wrong with the world.

Maybe. But sometimes I think we look too hard at the wrong things, or that we expect too much from things that aren’t perfect. Sometimes we just want something fun and pretty.